By the time the formal event began, every chair in the West Dallas Multipurpose Center was in use. The neighborhood group Singleton United/Unidos had gathered the community there to celebrate publishing a 100-page report detailing what they say is the high price of living near a shingle plant.

Their work was aided by the longtime environmental justice nonprofit Downwinders at Risk, whose director, Jim Schermbeck, scuttled about trying to find more seats. The mood was boisterous and defiant.

A sign-in sheet near the door was full, and as attendees tucked into tacos, Schermbeck’s colleague—and Paul Quinn College Urban Research Fellow and Professor—Evelyn Mayo addressed the crowd, serving as emcee alongside Texas Organizing Project’s David Villalobos.

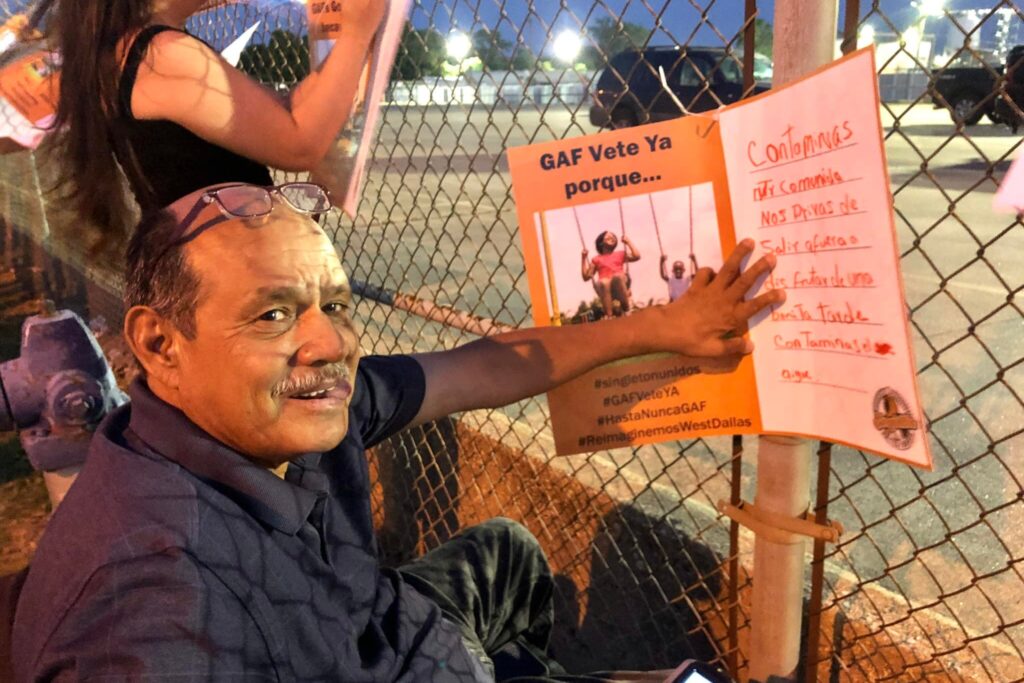

All told, close to 100 people showed up to talk about Singleton United/Unidos’ “Case for City Amortization of GAF.” They would end that May gathering by walloping on a piñata while a mariachi band played, then bringing their fight directly to the GAF plant on Singleton Blvd. They placed oversized postcards on the fence that proclaimed that “GAFs Gotta Go.”

For better or worse, the shingle plant directly across the street from the multipurpose center has been part of the neighborhood’s fabric since 1946, when it was operated by the Ruberoid Co. GAF, a New Jersey-based shingle manufacturer with 34 operations in 26 cities, merged with Ruberoid in 1967. Corporate raider Samuel Heyman won a proxy battle for GAF in the 1980s, and the company is now part of the Standard Industries roster of industrial manufacturing subsidiaries.

The neighborhood group’s report argues that the city should force the operation to move away from the people who live near it, citing zoning, health, and quality of life concerns. This is a process known as amortization—the city’s Board of Adjustments would declare the plant a nonconforming use, which would mean that the plant could be forced to leave the neighborhood.

To get to that point, though, Singleton United/Unidos will need to prove that the shingle plant is having an adverse effect on the people who live around it.

Group organizer Janie Cisneros said she is confident that the Dallas City Council will submit the group’s request to the Board of Adjustment, which will hold a public hearing to determine if the plant should remain at its decades-long address.

If the board approves the request, the plant could be shuttered if it does not agree to conform to the zoning the city chooses to apply to the area; a GAF spokesperson says the company will take the matter to court if that happens. If the board denies the request, the neighborhood group can appeal to a state court.

“This is something I absolutely think is very feasible and doable,” Cisneros said. “The whole amortization process is to prove adverse impact, and I’m pretty confident that what we’ve gathered shows that.”

Cisneros said part of the group’s confidence stems from the city’s own zoning for the area. The report argues that the plant should have been closed in 1987, when the city revamped its planning policies. Dallas tried to establish zoning rules that would protect neighborhoods from encroaching industry and other non-residential uses.

However, those new protections weren’t extended to West Dallas neighborhoods, or to some historically Black neighborhoods like Cadillac Heights in Oak Cliff. (That neighborhood later sued the city.) GAF and other industrial sites were allowed to continue operating. GAF, the group’s report said, should have been zoned for “light industrial” use due to its proximity to residential areas. The report is arguing that its current zoning as an industrial manufacturer of shingles would not be allowed near homes in most of the city.

The report identifies residential areas on Bedford Street; around the Multipurpose Center; and Kingbridge Crossing, just west of Fish Trap Lake. The Muncie neighborhood is just east of the plant, and several more neighborhoods are within a mile of it, including Ledbetter/Eagle Ford, Westmoreland Heights, Greenleaf Village, and Victory Gardens.

The group says this industry has caused a litany of health issues from its emissions, which range from breathing problems to throat cancer. They also say their quality of life has been impacted by the smells associated with shingle production. Being zoned for industrial use has also made it more difficult to get home improvement grants and loans, the report said, resulting in many families moving out of the neighborhood.

Last week, representatives of Singleton United/Unidos met with the district’s councilman, Omar Narvaez. Cisneros said that meeting was “very productive.”

“Omar is on-board to proceed with amortization and his office will work on scheduling a meeting with the city attorneys in June so we can discuss strategy and next steps,” she said. “We told him we believed him when he said he would be our gladiator and now we are expecting him to take action. It’s clear we both love West Dallas and are willing to do what is necessary to remove GAF from our community. I am very hopeful.”

Narvaez said he has “always been” in favor of amortization. The issue was brought to his attention in 2021, he said Wednesday, and he’s met with Singleton United/Unidos and other community groups since then.

“In January 2022 the city attorney’s office, Singleton United/Unidos, and West Dallas 1 met in a joint meeting to see how we could proceed as there were still pending issues for the lawyers,” Narvaez said. Cisneros said this morning that Singleton United/Unidos will meet with Narvaez and the city attorney’s office June 30 to discuss the next steps for amortization of the GAF plant.

After decades of living next to the plant, Cisneros said her neighbors are ready to fight, especially in light of recent successes from other environmental justice activists in the city who fought for their own neighborhoods. She points to Marsha Jackson, the homeowner who raised awareness of Shingle Mountain, an illegal shingle dump next to her house that grew to over 70,000 tons before it was recognized by the city. It took over a year—and multiple court hearings—to have it removed. The city is now remediating the land and stakeholders are working with the charity arm of HKS to develop plans for a park.

“I do think that right now people are paying attention, and I’ve got to give Marsha Jackson a big thanks for paving the way with what happened with Shingle Mountain,” Cisneros said. “I definitely think that more eyes are on this … dialogues have already started with people at all different levels of government.

“Communities are fighting and are building coalitions and supporting one another, too,” Cisneros said.

The residents near the plant are using Purple Air monitors to record airborne particulate matter. They say those 24-hour daily averages either meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s annual standard, or are close to it.

Paul Quinn College’s annual pollution report in 2020 found that the factory was the second largest source of PM2.5—a fine particulate matter that, when airborne, can cause a variety of ailments—in Dallas County.

But a spokesperson for GAF says the company says the plant is in compliance with EPA regulations established by the Clean Air Act.

“GAF takes compliance very seriously, complying with requirements in the facility’s Federal Operating Permit, underlying construction authorizations, and applicable state/federal air regulations,” the spokesperson said, insisting that the company’s pollution controls are considered the best under its permit, and “also meets the higher standard, Maximum Achievable Control Technology, for its pollution controls” even though it’s not required of them.

“The neighborhood highlights the risks associated with various pollutants while completely ignoring the fact that GAF complies with regulations specifically designed to address those risks,” the company said.

It also takes issue with how the neighbors are monitoring air quality, saying that Purple Air monitors are “not very accurate.”

The city of Dallas has recently approved the purchase of 24 air monitors, some of which will be installed in the neighborhoods near the GAF plant. Carlos Evans, the director of the Office of Environmental Quality, says the city is working with residents to determine where to place them.

The conflict between industrial sites and their neighbors is not a new one—even for Dallas. All over the country, cities are grappling with what to do when a mix of lax (and race-based) zoning, longstanding businesses, and community members are in conflict. Do communities, now feeling empowered to insist differently, have the ability to shut down a shingle plant that has operated in the neighborhood for decades?

“Some of this is very historical,” said Dr. Barbara Minsker, a professor at SMU’s Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity. “Fighting these kinds of dirty facilities in low-income areas, it’s a long tradition partly because the people are less likely to complain about it, and sometimes they want the jobs that might come with it.”

But when residents around that site decide they no longer want to live near it, cities are often dealing with two dichotomous issues.

“So Dallas would have to be the facilitator, and the advocate for the community,” she said. “But in a way, they’re in a competing position because they also want the industry to be there to provide tax revenue and jobs.”

Minsker said that it can also be more difficult to prove that a specific plant is producing all of the pollution and emissions in a neighborhood, especially if that neighborhood is in an urban area and there are also other industrial plants nearby.

“There’s always the political route, like they did with Shingle Mountain,” she said. “You just keep raising enough of a stink until eventually someone takes some action. But in that case, it was very clear where the contaminants were coming from.

“If this group (GAF) can say, ‘You know, we’re meeting our permitted levels, we’ve done our part,’ it’s going to be harder to make an argument that they should leave.”

Which is why Cisneros and her neighbors aren’t just focused on the pollution, but also what they say is a case of mistaken zoning from decades ago. The city is currently writing a new land use policy that will dictate what can operate and where. The group believes now is the time for the city to rectify an oversight from more than 35 years ago when Dallas failed to zone their neighborhood appropriately and equitably.

“This is a really, really good time to press on these issues moving forward,” Cisneros said. “You’re already forming a vision for the future of Dallas and incorporating all of these plans, including the neighborhoods and their plans. And none of those plans are for polluters (to be) in their area.”

GAF submitted a response to questions in a PDF, which you can read below.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author